This entry is an activity for Teach-Now while working towards a teaching certificate. Specific goals and requirements had to be met by this entry and is by no means designed to be an independent feature.

Exploration of formative assessment for visual art learning

An important skill for artwork making is visual perception. A visual form requires a plastic or an organic construction based on the seeing-sense perception and the application of relevant principles and techniques. That application is essentially your interpretation and translation of what you have seen into a product. Thus, art-making can become very subjective. Viewing artwork means the viewer has to know and understand art principles, the art context and the artist’s personality, thinking and emotional moment. While doing all of that, the viewer using their own seeing perception, critical thinking and knowledge develops their own interpretation and translation. Thus, art is not easy to evaluate.

Evaluating art made by art students will need exact and special consideration using two types of assessments. Students should learn—if not know— the basic foundations to create. However in professional practice, art becomes a message that subjectively conveys a person’s condition, emotion, and interpretation of what they perceive either mentally or visually. But in the introduction of art making, students will have to study and practice basic applications and provide their knowledge in physical evidence. Assessing their success to demonstrate that goal will be based on the result and the process making that result. How well students copy what they see with regards to their intent, and how well they utilize art techniques to render what they see will be the summative assessment for their effort. The process of copying what they see and working within that process will be involve formative assessments.

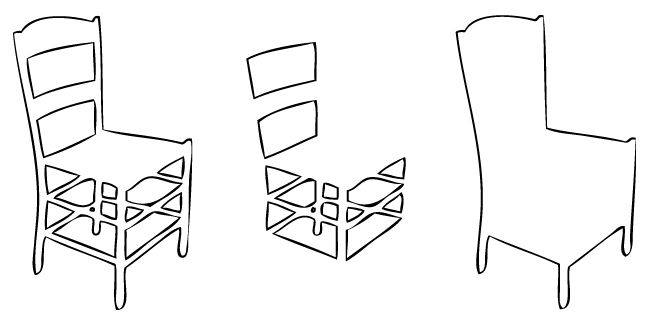

One objective for visual arts in New York supports a standard demonstrating that students will be able to make works of art. Students will need to render a clear representation of an observed object based on negative and positive space viewing shape, tone, value and texture to construct an object. When working on just the silhouette, the student only needs to work with positive and negative space using the contour in between. The silhouette renders should closely resemble the object they have observed. Their lines and value show execution with intention, effort, and thorough thoughtfulness.

Whoa! What did I just say?

If we want to evaluate the progress, the standard objective’s rubric will be the foundation for formative assessments.

Did the students:

- …render in their medium of choice a sound silhouette realistically matching the object they copied? Meaning, can it be identified or at least visually fit to what I see when I squint my eyes to look at their subject? (Squinting removes color and reduces value to an almost solid tone.)

- …render with practiced gestures that suggest smooth technique application to create their visual copy? Or are lines and shapes built with care and with respectful effort?

- …honestly testify to their visual thinking with the proper art language related to the activity? Can they say, “I concentrated on one negative space to create a basic unit that constructed other shapes proportional to the first.”

Art by intrinsic nature is its own assessment. The final production becomes the proof of effort. The artwork you see defines the product’s intention, effort, materials and process. The question will be does the student know what they made and why. Relying on Terry Heick’s list of 10 assessments, one form of evaluation is “Draw It. Draw what you do understand (Heick, 2013).” The student will draw what they understand by how they draw and what they see — the product and the process of the product will be its own presented evaluation. That is not to say that evaluation will only occur at the end of the project.

The entire moment of creating provides moments of evaluation by both the student for themselves and for the teacher. We call these moments critiques. Critiques are simply conversations between two or more people (generally artists, but not necessarily so) reviewing the artwork and/or its process. In the case of visual art learning, teachers can discuss with the student the project’s process evaluating its progress to the intention. The evaluation happens with assessment formulas based on questions, comparing it to the project’s goals, and the overall regard of the render itself using words that productively describe it providing answers. Conversational reviews during the art-making process will be one of the formative assessments. The words and evaluation may have some negative comments, but consider that conversations can be productive. Heidi Andrade (et al) stated that formative assessment provides three simple benefits:

( 1 ) An understanding of the targets or goals for their learning;

(2) knowledge of the gap between those goals and their current state;

and (3) knowing how to close the gap through re-learning and revision

Essentially students learn of their progress. How do they do that? By students reviewing work through discussing whether specific goal techniques exist, to what degree they exist, and what revisions could be applied to reach the goal. During their evaluation, students also grow their subject knowledge and their art communication. By implementing art language and terms relevant to the goal and inspired by the artwork, students gain art knowledge. After receiving feedback from their peers, students should have enough for their next step. They should be allowed to explore and re-assess these statements for their validity. Did this conversation provide input matching my need? Does any of this information make sense? Also, the student evaluates what observations would be helpful for their own work. What information will help them to achieve the goal toward their own intention? Critiques become an art technique for formative assessment. While talking about work, students practice art’s scientific language.

Andrade’s observations provided another example. While working on a printmaking activity, students were encouraged to write observations of problems and solutions during their process. To help with developing a new understanding of printmaking and art making, they had to interrupt their work and record their process and progress. The idea of interrupting thinking to think seems contradictory, but the process appeared to be helpful. Samples of success and mistake prints were presented with their reports. Presenting their mistakes encouraged them to learn what went wrong and what next steps they could do to revise or make another attempt to their goal. Again, conversational critiques between peers revealed another perspective of the developing project. Critiques would provide input of whether the artist (the student) was working to the intended goal or to discuss revisions that will work toward that goal. These conversations also provided an arena to practice art language. With the process of class critiques, students work on peer- and self-monitoring. By students participating in conversation of evaluation, they become their own teachers for themselves and to each other. These moments become formative assessments both for the student from students and for the teacher to evaluate the awareness of the skill’s degree of quality and the process and practice of art making. Basically, the important element of this process is periodic critiques to review the progress and technique application success during the art making and not simply just the summation review of the final piece. This type of formative assessment provides frequent feedback of the students’ measured skill.

During the lesson. The walk about’s can provide a clear view of how students feel or know what they are doing. Walking around and observing students during their work demonstrates if students understand the concept enough to build more knowledge through practice. I can ask a question that establishes a curiosity of what they currently know regarding the activity. One question may be fine, but it may not completely provide full confidence that they know it nor may it really mean that they know it. I want to be sure and I want them to be sure, so I intend to follow-up questions with questions (Dyer, 2013). The questions should be designed to seek a common understanding but not lead students into giving the expected answers. Questions should be designed that exercises thinking. In a classroom discussion, teachers select a student to answer the first question if an answer was not volunteered. But, the questioning does not stop there; the teacher asks another student either a more exploratory question deepening the subject inquisition or ask if that answer is correct. Continuing on, the questions could further explore the debate or have more explanations that engage students into discussion as well as each one self-prepares an answer on the chance they are selected. In a single-student situation, the questions drill to explore deep understanding of not just what, but how and why towards a bigger what.

At the end of the day. Students can provide additional responses beyond the art piece—the exit ticket (Teacher Toolkit). Exit tickets are exactly what they are: a note, response, or question submitted by the student collected by the teacher at the end of the session. An exit ticket could be “how did you do?” but with such a vague question the answers will not support a specific concern. A better question would be one that incorporates the lesson’s goal as the question or expectation. Exit tickets will provide another form to confirm knowledge gained, evidence of questions or not understanding, or of any other response. Beyond questions, the exit ticket could simply be a poll of how the students feel about the activity. In the end, the data can very useful. They provide how to: start/differentiate the next lesson expanding on any needed knowledge; design a different lesson providing an alternative perspective or explanation; or completely remove that lesson and find a new way to explore the goal. Allow students to express themselves in different ways beyond the work itself.

The final end. The whole term is summed up in one final development, the final portfolio. The portfolio becomes the summative assessment. Does the portfolio provide sound evidence of actual progress developing better and better art making? Each piece should build on previous knowledge practiced on previous pieces. Did the student work with honest effort? Do all pieces show a polished result that equally convey intentional making? Can I see growth of a student’s desire to learn and maintained motivation? Certainly, art products are subjective. The student’s work should not be the only element to assess the whole process. I may not see the intention as intended. Students can write their own reflection and response after each artwork providing another formative assessment for me to view. During each step of the term, their reflection can provide evidence of their skill confidence, practice, and knowledge as they see it during that moment when it is fresh and not tainted by time.

Art is difficult to assess. Formula evaluation can be somewhat not pragmatic in visual arts. The art techniques, vocabulary and principles can be studied and are concrete; but the subjective application becomes hard to evaluate. Why? Art is a personal reflection by creative expression. Assigning any negative evaluation may discourage future efforts; negative comments may dismiss the value of their participation to visually communicate. The language will have to be carefully delivered to provide constructive observations encouraging more development. The artwork itself will not be enough to grade. Careful language and approach during critiques, learning students perspectives by exit tickets, on-going questions for deeper answers, and periodic written reflections provide the wider explanation that present whether the student practices confident knowledge or mistaken interpretation.

I know I stated that an important skill for art making is visual perception, but one aspect of visual perception is the observation of space. A differentiated set of activities can be designed to challenge the perception of space for those without sight. These exercises would still involve the use of negative space and space around the object to construct the object itself. Tactile responses to the object can be harnessed by the extent of how soon the body meets the object and other parts of the object. The artist will still respond to the space in between to create the whole.

References:

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson, 1983.

Andrade, Heidi; Hefferen, Joanna; and Palma, Maria. (January 2014). Formative Assessment in the Visual Arts. Art Education. http://art407.weebly.com/uploads/5/9/2/6/5926741/formative_assessment_in_the_visual_arts.pdf

Dyer, Kathy. July 12, 2013. 22 Easy Formative Assessment Techniques for Measuring Student Learning. (Teach. Learn. Grow. The education blog). https://www.nwea.org/blog/2013/22-easy-formative-assessment-techniques-for-measuring-student-learning/

Heick, Terry. (March 14, 2013). 10 Assessments You Can Perform In 90 Seconds. Teachthought. http://www.teachthought.com/teaching/10-assessments-you-can-perform-in-90-seconds/

Teacher Toolkit, The. (n.d.). Exit Ticket. the teacher toolkit. http://www.theteachertoolkit.com/index.php/tool/exit-ticket